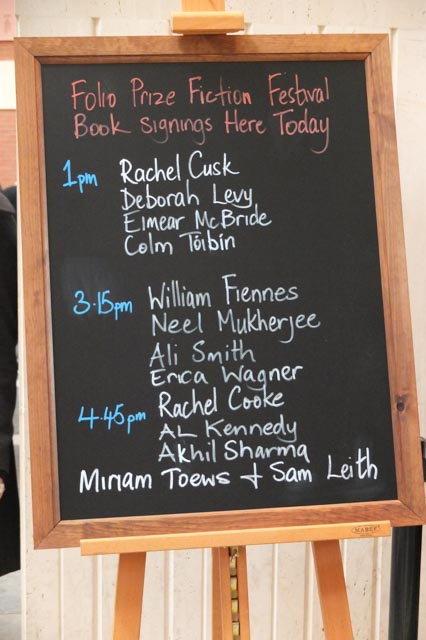

Last Saturday I attended part of the 2015 Folio Prize Fiction Festival at The British Library. The festival is an event designed around the announcement of the Folio Prize http://www.thefolioprize.com/ which is awarded “to identify works of fiction in which the story being told and the subjects being explored achieve their most perfect and thrilling expression.” The festival itself was devoted to exploring the art of storytelling.

I attended three panel discussions: On Desire, On Conflict and On Wit.

The first discussion, On Desire, involved authors Rachel Cusk, Deborah Levy, Eimear McBride and Colm Tóibín in discussion with the critic, journalist and broadcaster Alex Clark. They had several interesting points to make on how desire influences our stories, our characters and even on how desire affects us as writers.

Colm Tóibín made the point that his writing life begins with his reading life.

Of course, all writers begin by reading. Initially we read because we enjoy it, we find it fulfils us in some way. Reading can be an escape and an adventure, amongst other things. After doing a lot of reading we may progress to wanting to create our own stories. But after we’ve begun writing, maybe even taken some classes, there is the tendency to think about our reading—and writing—more consciously. Who are we writing for? Who will read our books after they’re published and how should we think of these readers when we are writing the story? There is no simple answer to this question.Is the solution then to write the types of books we would like to read?

One of the speakers said that it is the desire of a character which opens up the space with which to explore them and their story. The characters, like us, have immediate desires they would like fulfilled as well as distant hopes and it is from these that we can build a story. With each new desire you give them, there are opportunities for them to pursue, ways we can thwart them and it is by this process that readers will continue to turn the page.

Colm Tóibín said that a novel is comprised of 2000 details and a writer doesn’t know all of them before he/she begins writing. It might be one small detail which sets the others into motion. He compared writing a novel to painting, where you fill in the complete picture one brush stroke at a time, slowly crafting your writing in such a way that it tells the story you want it to. He said the writer needs to surprise themselves, but not too much.

I suppose this is the same as saying that whatever type of writer you are–a planner or one who discovers while writing–you should have some idea of where you are taking the story. But writers should also be open to changing direction where it seems necessary. Our characters and plot lines are not static and will evolve over time. We have to be willing to allow them to grow as they see fit.

This can be difficult to do. In one way we are controlling the work, and in another way the work is controlling us. How can we trust that it is going in the right direction? I suppose that is what Deborah Levy meant when she compared writing to a snake charming act, in which the writer is both the snake as well as the charmer.

When we rewrite our work we shape it, we discover what works and what doesn’t and sometimes we make mistakes. The more experienced we are at writing and rewriting, the better our judgement becomes—hopefully anyway!

From left: Eimear McBride, Rachel Cusk and Deborah Levy signing their books at The British Library Folio Prize Fiction Festival.

The second session I attended was On Conflict and involved the writers William Fiennes, Neel Mukherjee and Ali Smith in conversation with the American author and critic Erica Wagner.

It was noted at the beginning that all our lives are made of conflict, the engine on which fiction runs. Therefore there is no book without conflict.

The authors discussed the different types of plot and how these drive fiction. William Fiennes said that it isn’t always a clash which drives a story, it can be something which is nudged off kilter in a character’s life and the suspense might revolve around how things will be made whole again.

One of the things I found most interesting about this session was the discussion around what happens to a book after its been published: how is the author to think of it, to respond to readers perceptions of their book? Ali Smith said that the point of books is that you finish them, send them off and hope they’re ‘seaworthy’. Readers will make of them what they will, and if they go back and read them later they will probably interpret them differently, the way we would upon rereading a classic. As we change and grow so does the meaning of a text.

William Fiennes went on to say there is no such thing as a misreading of a work. If people read and respond to the work in ways the author had never considered then they are only interpreting the work creatively.

This discussion particularly struck me as my novel, The Forest King’s Daughter, has recently been released. It being my first novel, I am not sure how readers will interpret the story, how they will respond. I would hope they enjoy it and find meaning within its pages. As it is now published, I no longer have any influence over this. However, one of the things the writers did not discuss was the role of the author post-publication. As many writers now are responsible for some—if not all—of their publicity, do they still have some say in how the work is received?

The final session of the day was On Wit, with AL Kennedy, Miriam Toews, Rachel Cooke and Akhil Sharma in conversation with Sam Leith. They discussed the difference between wit and humour (they seemed to conclude there wasn’t one) and the role humour plays in fiction writing. AL Kennedy said it is just another response to tragedy ‘there’s fight, flight and funny’. She also said that humour can give an illusion of authenticity.

Akhil Sharma said that humour gives the reader distance from tragedy, it makes things less real. He compared humour in a story to the use of a spice in cooking—it makes certain things ‘just pop’. He said one of the reasons that Pushkin was the best of the Russian novelists was his use of humour which is a sophisticated response to human tragedy and something writers can use.

However, AL Kennedy warned that if we are not naturally humorous people, our writing won’t necessarily be so. She said that with any art, the key is to find out who you are, and to tell stories in the way you find most natural.

This session was particularly intriguing—and enjoyable—as I had not really thought about the role of humour in a story until now. I don’t know if I will be consciously attempting to infuse my writing with humour in the future, but I do like a story to be well rounded and this includes having some light-hearted moments. The session itself was very funny and I found myself laughing out loud at some of the anecdotes the writers relayed about their own writing and lives.

At the end of each session there was the opportunity to purchase books and get them signed by the authors.

I purchased On Writing by AL Kennedy, as I had been meaning to do so for some time.

She even signed it for me!

This was the first fiction festival I’d attended, and I did not know quite what to expect. By the end of the day I found I had an entire notebook full of reflections, observations and thoughts I wished to explore. There were so many ideas I took away from the discussions, and questions which had not yet formed but which I will be thinking about for some time yet.

Have you been to any fiction festivals or writers conferences? If so, what was your experience of them? What did you take away, and did they change your mind about any deeply held opinions? What do you think of some of the topics I’ve raised here? I’d love to hear your thoughts so please leave a comment below!

Oh yes, and I should say that the winner of the Folio Prize was Akhil Sharma for his book Family Life.